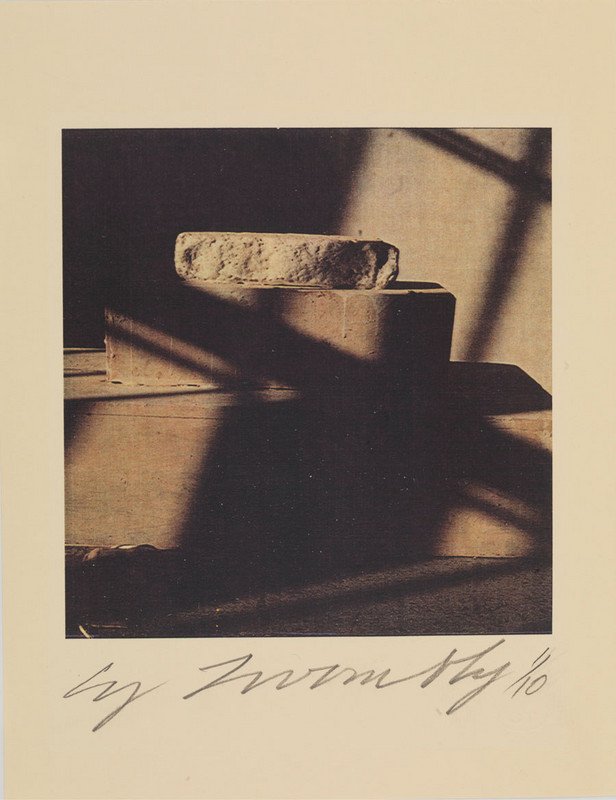

Photographs by Cy Twombly

Photographs by Cy Twombly

A Kind of Aura

by Edmund de Waal : Preface to "Photographs" Exhibition Book by the Gagosian Gallery (2012)

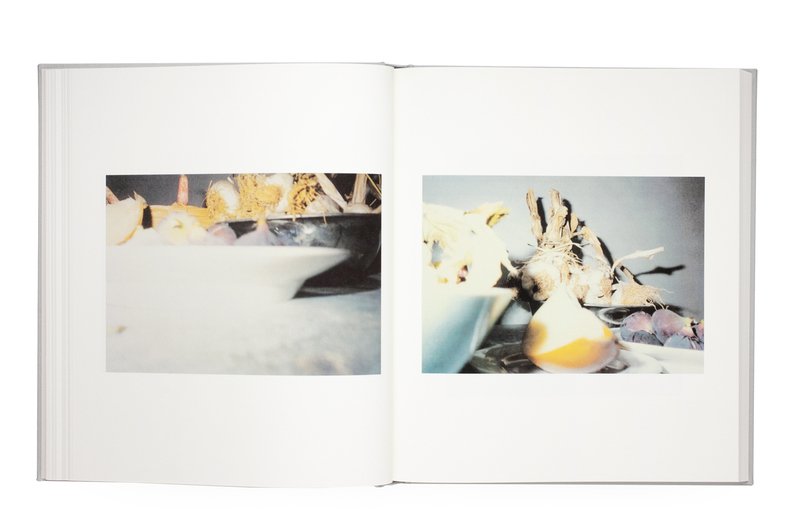

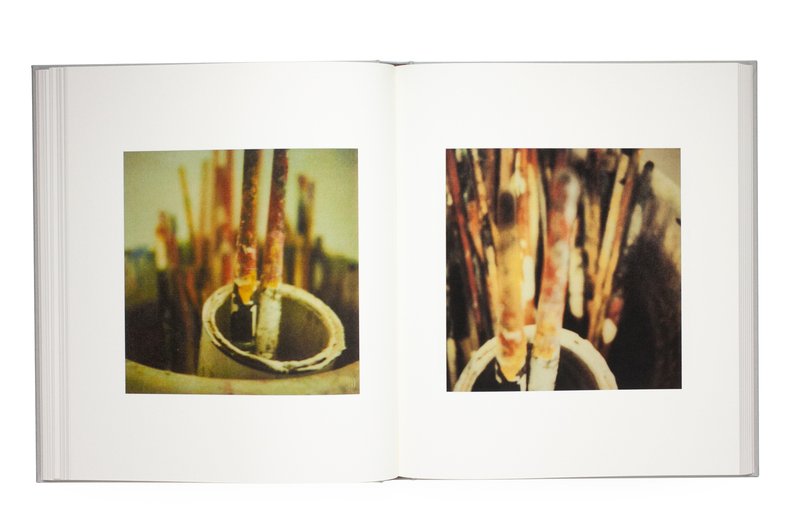

I didn’t know these photographs. But looking at them spanning a wall of a light-filled gallery, I felt the extraordinary presence of the man who took them, the late American artist Cy Twombly. He inhabits them. Spending time thinking about why this should be, I kept returning to the way he shapes memory. His paintings and sculptures keep alive very particular moments in their making, the inscribing, daubing, and scratching onto paper, canvas, and plaster, the sticking and tearing and collaging. His work is a glorious list of transitive verbs, an iterative inhabitation of the present moment. I’m here, says this art, here and now. And all to bring into this moment a sense of time, stretching from here to Apollo, through his own memory of music and poetry, architecture and painting.

And memory is at the heart of these photographs. They span 55 years, from the early photographs of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combine Material in the Fulton Street studio – cloth, wood, and detritus heaped, piled, and stacked in anticipation – to moments of sky, a cloud touched by pink and grey, taken just a few months before his death. His photographs of bouquets of flowers left on a grave, Polaroid lilies and roses, are particular to a moment of privacy staged in public. The flowers, poignant in their extravagance, become a kind of testimony. In the image of a yard sale in Lexington – a jumbled collection of abandoned objects, a watermelon, a jar of marbles, kitchen implements – objects become as memorialised as Homer’s thousand ships.

At the heart of these photographs, just as in his paintings and sculptures, is the act of putting something aside, an act of apprehension and record. This has a good Greek name: anathemata. In Twombly’s sculptures, plaster, wood and wire become, through this act of anathemata, a pyre or a stele. They become an inscription in space. And like a palimpsest, where one text lies upon another, the vellum having been scraped back but still containing the hours of writing that had been there before, they seem to be a memorialising of time itself. When looking at these images, you are aware of this act. Trays of cakes in the window of a shop in Boston, rows of small baroque confections, have the same significance as the fragment of a classical marble.

They seem to go to the heart of memory, its instability, the contingency with which we live. We remember a beach in summer, a line of umbrellas between us and the sea, an impossible blue haze as in a painting by Boudin. This photograph takes that moment and gives it a pause. In this way they are as lyrical as the poems of Rilke, to which Twombly returned with such intensity and affection. For Rilke, poems were epiphanies, revealing moments of transition when the world becomes alive – a dancer’s first movement is the flare of a sulphur match. In his poems there is a kind of unsteadiness on the edge of life, like a swan before an “anxious launching of himself/ On the floods where he is gently caught”. But for Rilke there was also sense of the shape of poems: they were objects in themselves, Dinggedichte, thing-poems. The longer I spent with these wonderful photographs, the closer I felt they were to thing-poems. I look at Twombly’s lemons and see lemons for the first time.

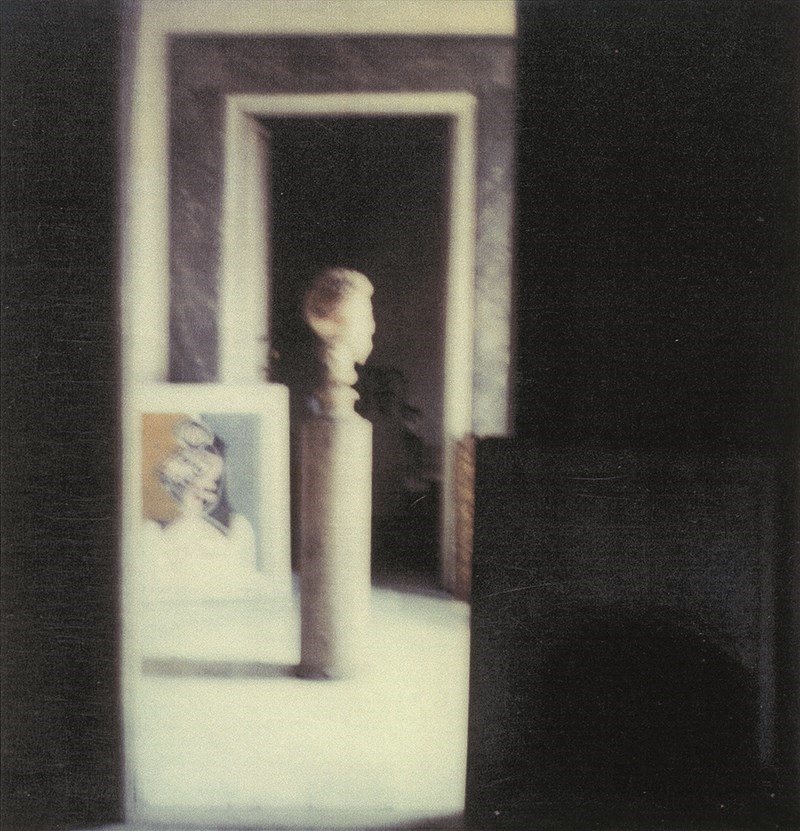

And spending time with these images made me wonder about what it is like to photograph a sculpture or a painting: to make one image out of another. For some of the most haunting of his photographs are of details, part of a figure, an unfinished picture. This is where there is the greatest intimacy. It reminded me of Man Ray’s description of his encounter with Constantin Brancusi:

“I went to visit Brancusi with the intention of taking his photograph so that I could add it to my collection. He frowned when I broached the subject, saying that he did not like having his photo taken… Then he showed me a print [Alfred] Stieglitz had sent him during the Brancusi exhibition in New York. It was one of his marble sculptures, and both light and grain were perfect. He told me that although it was a very beautiful photograph it did not embody his work, and that only he could do that. He then asked me whether I would help him procure the necessary equipment and give him a few lessons.

“I replied that I would be more than willing to do so and the very next day we set off to buy a camera and tripod. I suggested he take on an assistant to develop the photos in a dark room, but this too he wanted to do himself. And so in a corner of his studio he set up a dark room… I showed him how to take a photograph and in the dark room I showed him how he should develop it. From then on he worked alone and never consulted me again. Soon after, he showed me his prints.

“They were blurred, over- or underexposed, scratched and stained. ‘There you are,’ he said, ‘that’s what my work should look like.’ Maybe he was right – one of his golden birds had been photographed with the sunlight falling on it, so much so that it emanated a kind of aura which made the work look as though it were exploding.”

Twombly’s photographs share Brancusi’s intensity of vision. They have an aura. Remembering the image, the sound, a footfall, the passage of light across a bowl of roses. I find them incredibly moving.

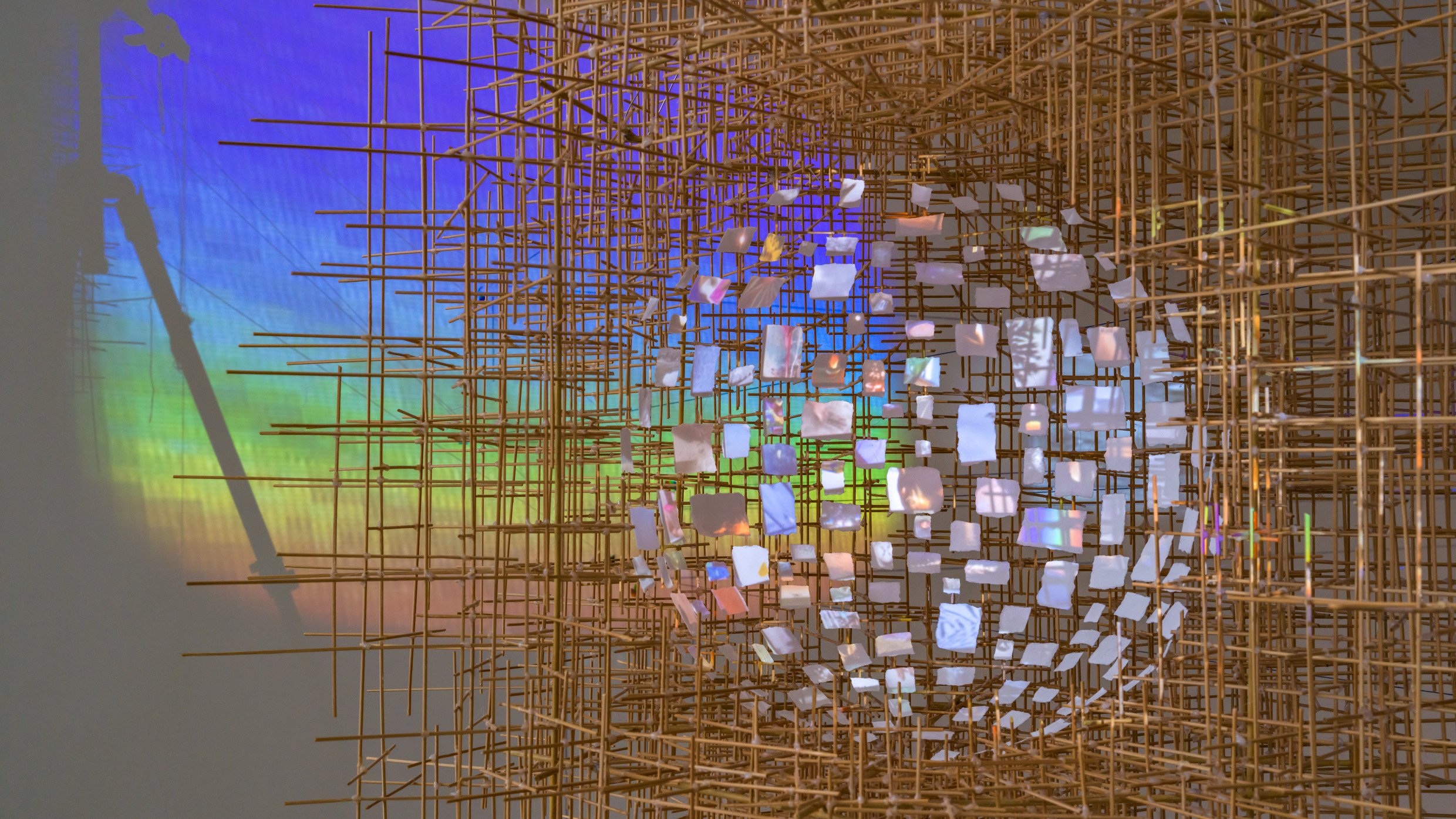

Timelapse with Sarah Sze

Timelapse with Sarah Sze

For this solo exhibition, Sze created a series of site-specific installations that weave a trail of discovery through multiple spaces of the Guggenheim’s iconic Frank Lloyd Wright building. Outside, the exhibition spills into the public sphere beyond the museum walls. A flowing river of images traces the building’s exterior, echoing the movement of the traffic and passersby at street level, while a live-feed projection of the moon on the curved rotunda facade will mirror its cycle over the course of the exhibition. In Sze’s reimagination, the iconic UNESCO World Heritage architecture becomes a public timekeeper in a reminder that timelines are built through collective experience and memory…

Time, as it unfolds the ensemble of works gathered for Sarah Sze: Timelapse, is not only a collection of lived and remembered experiences but, in the words of the artist, “a contemplation on how we mark time and how time marks us.”

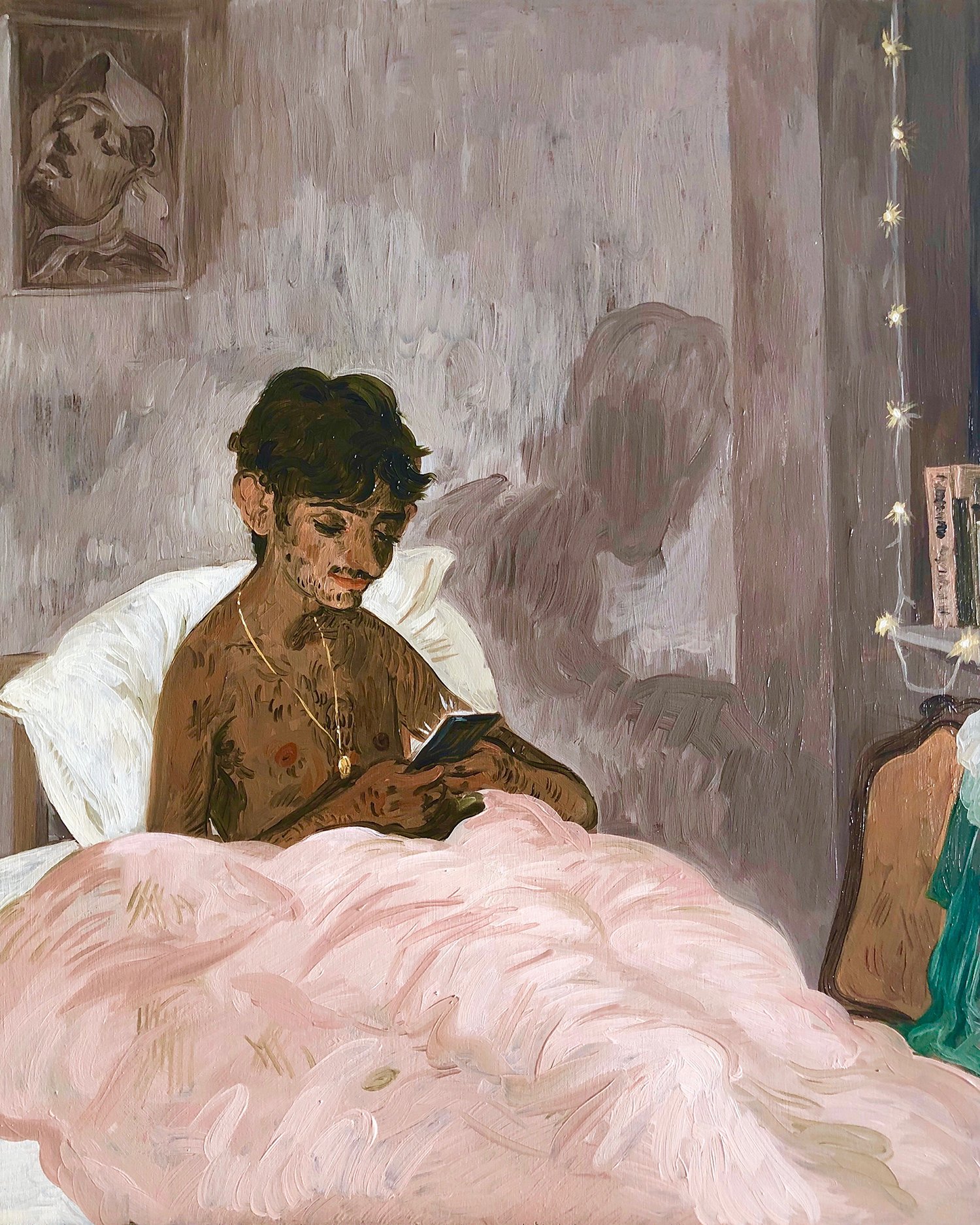

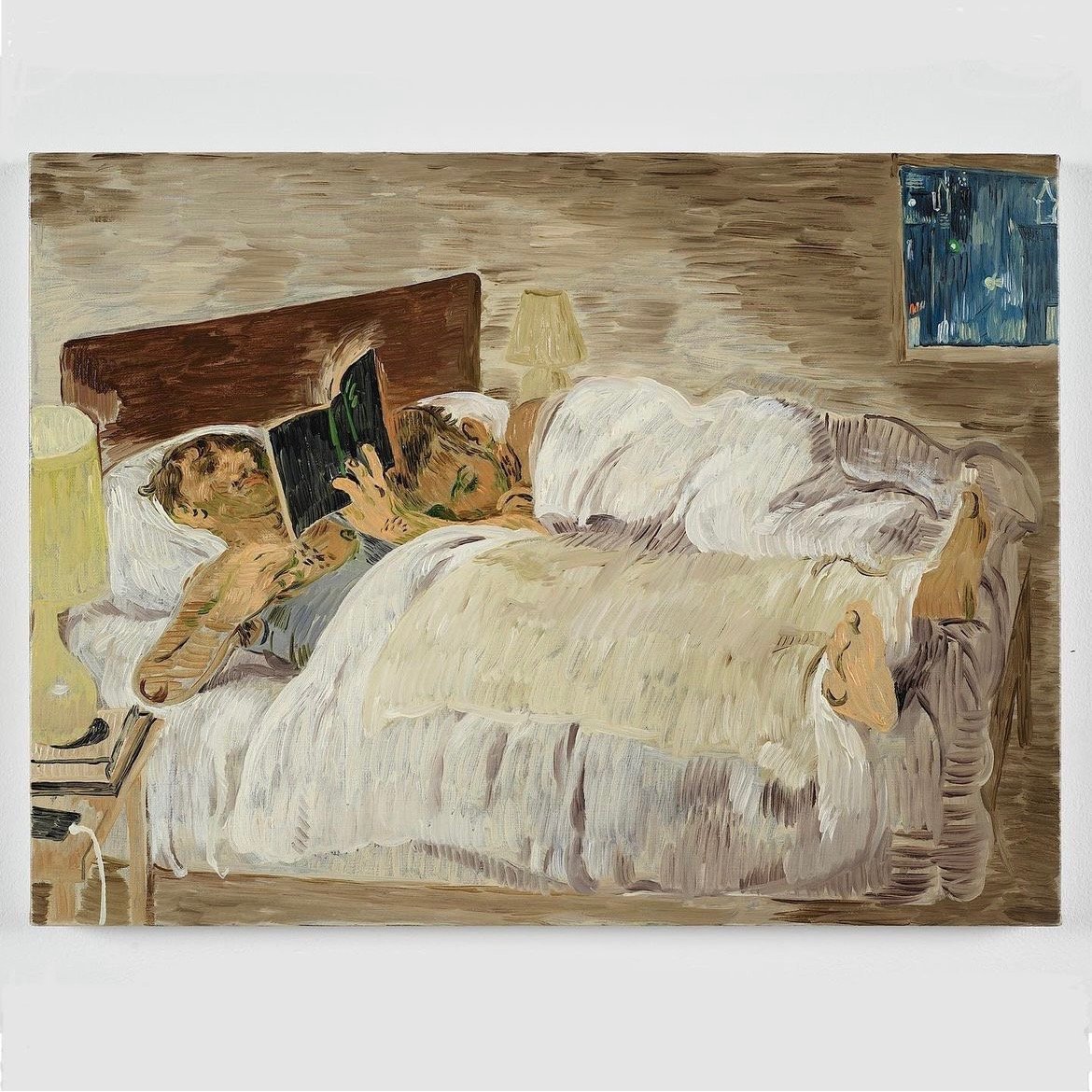

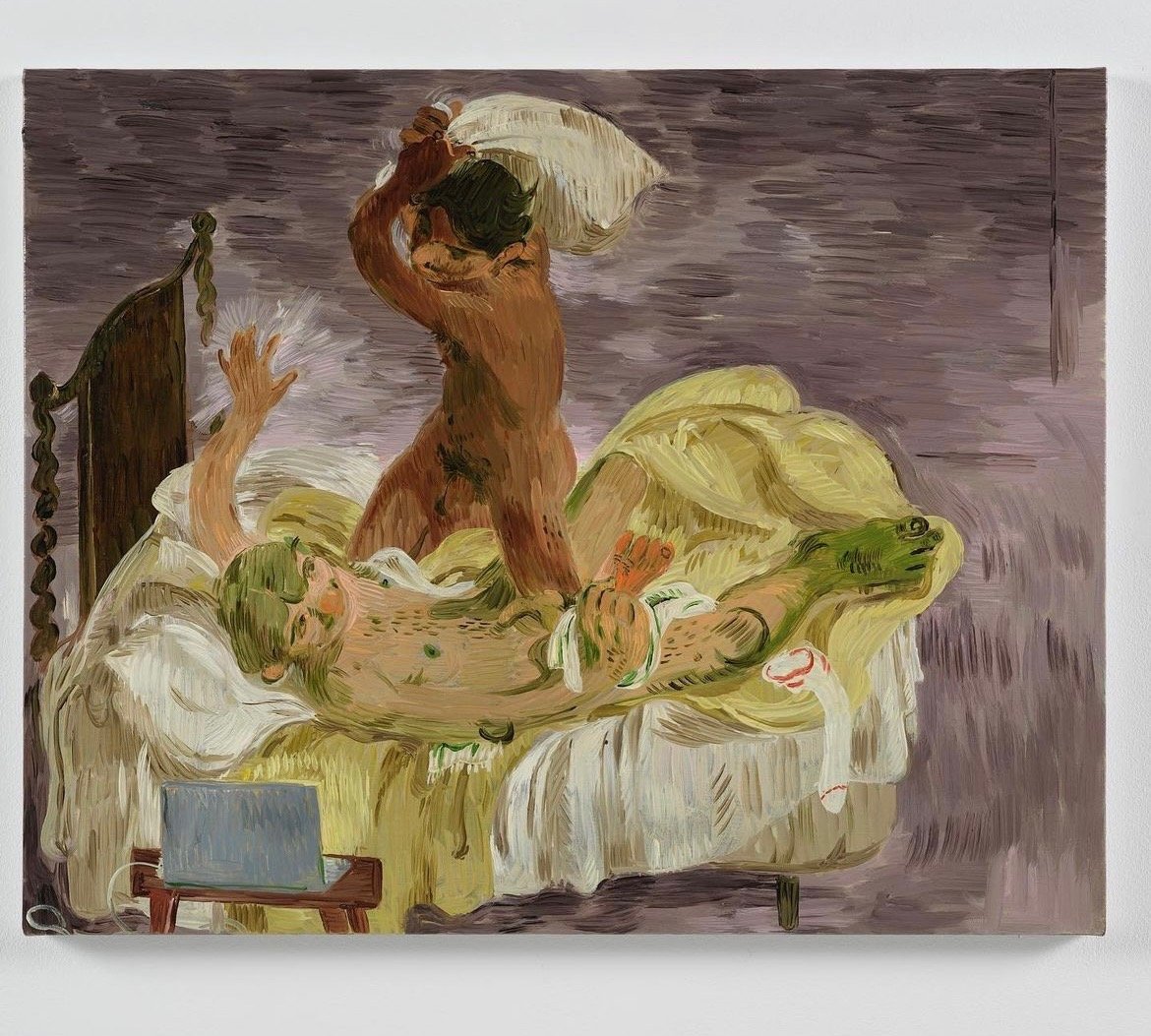

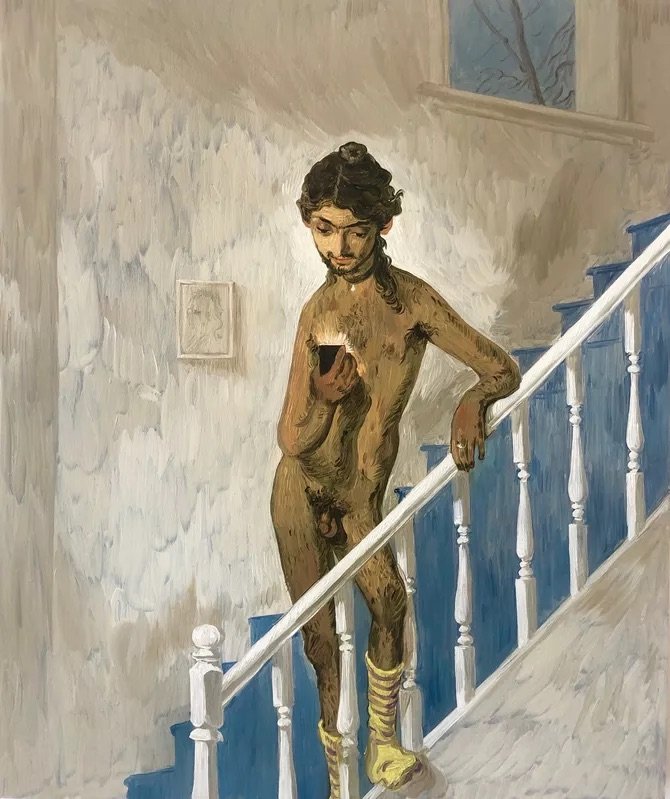

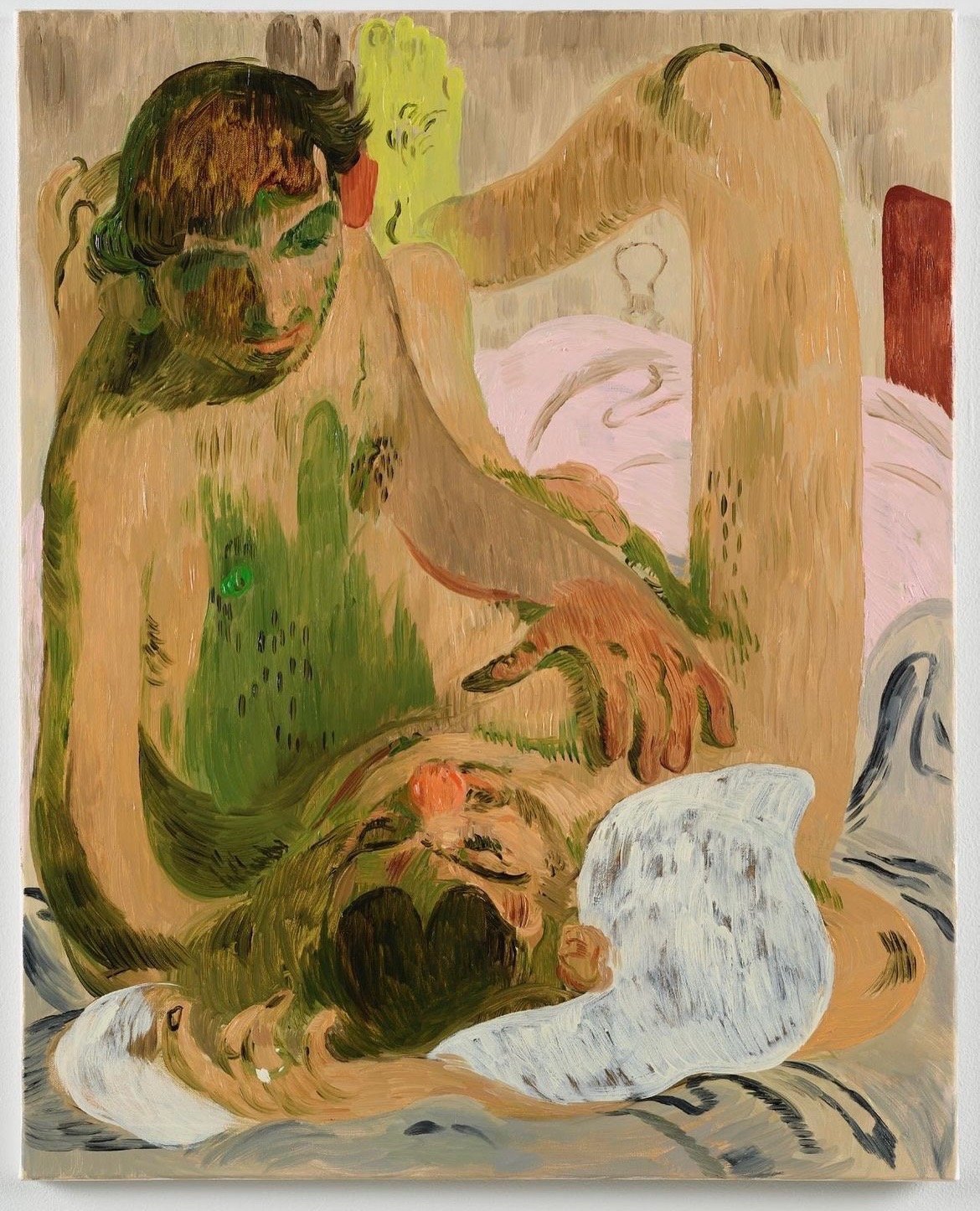

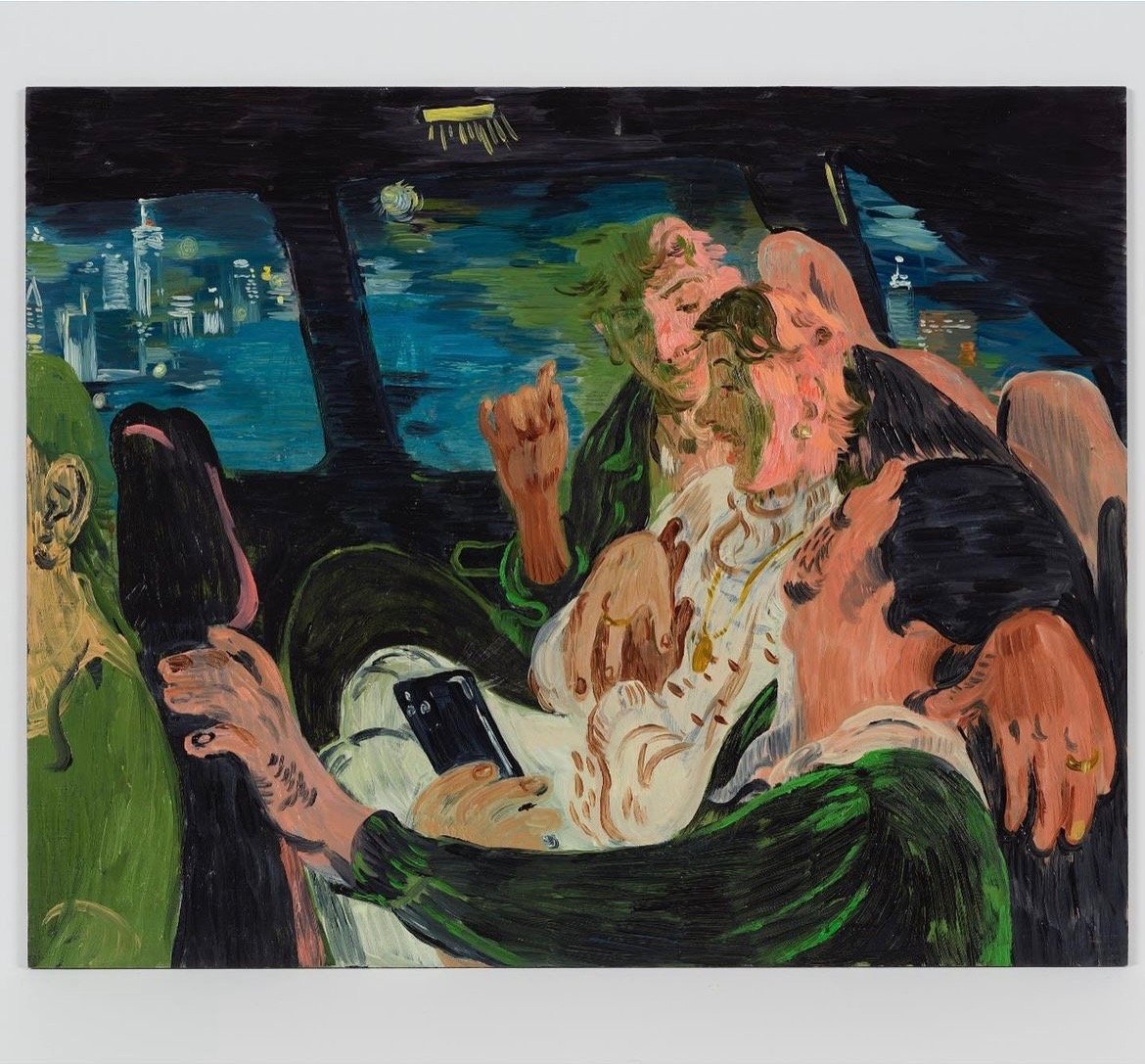

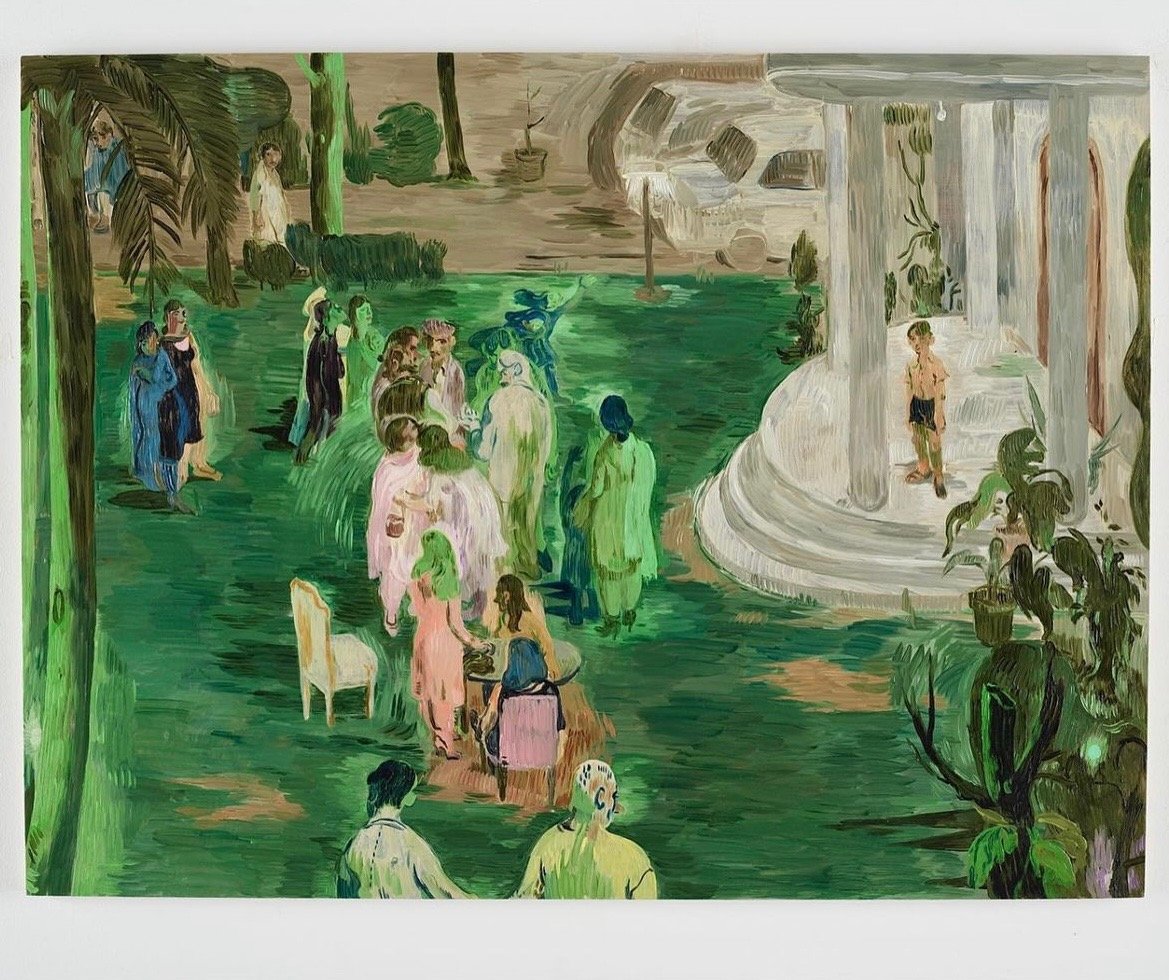

Blurring the Lines with Salman Toor

Blurring the Lines with Salman Toor

I like these seemingly undernourished and hairy bodies of color inhabiting familiar, bourgeois, urban, interior spaces. I see these boys or men as well-educated, creative types discovering what it means to live an artist’s life in New York City and in the thick of changing ideas about race, immigration, and foreignness, and also what it means to be American. Sometimes they can look like lifestyle images. They are also fantasies about myself and my community. It’s incredibly empowering to share the comedy and disquiet of these narratives with Americans, and the world…

I (also) enjoy that technology blurs the line between public and private. Lonely in a room full of people, over-connected but all alone in a silent apartment, drinking up the screen intimately with a friend or lover in a dark bar. I’m excited by the cell phone as a source of intimate light. It’s the light in which people read, look—together or alone—with that resting face. In these moments they have the intimacy of one of Vermeer’s letter readers.

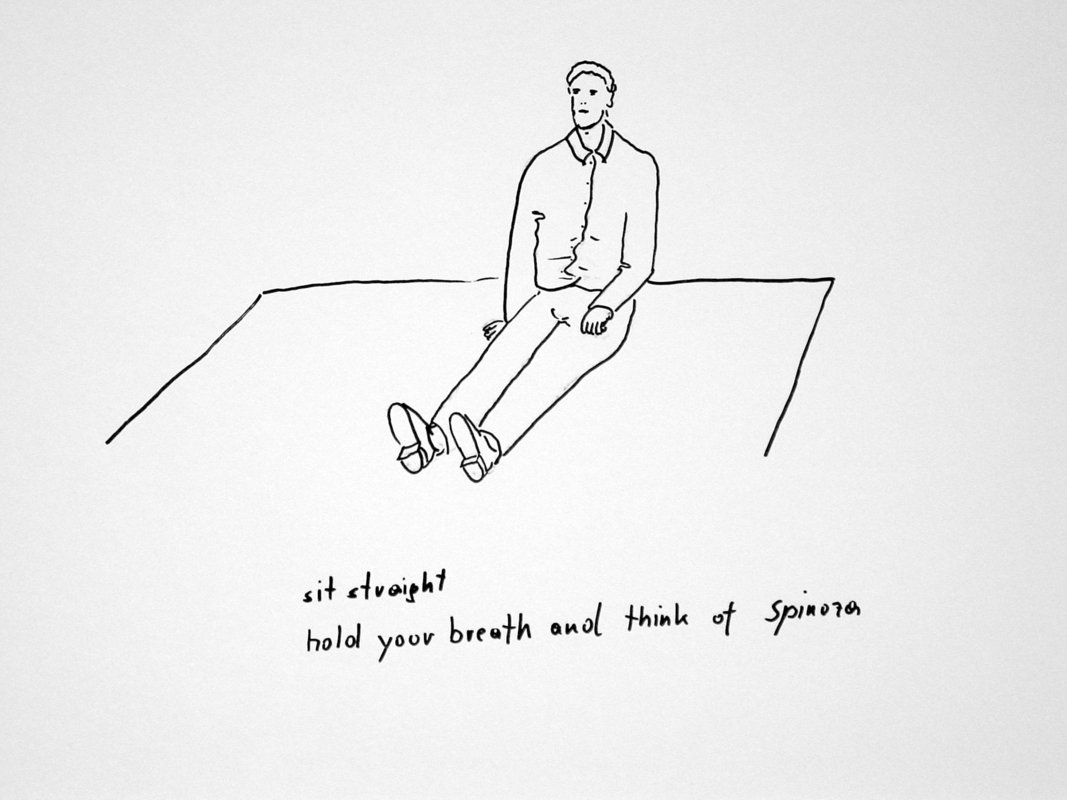

Erwin Wurm

One Minute Sculptures

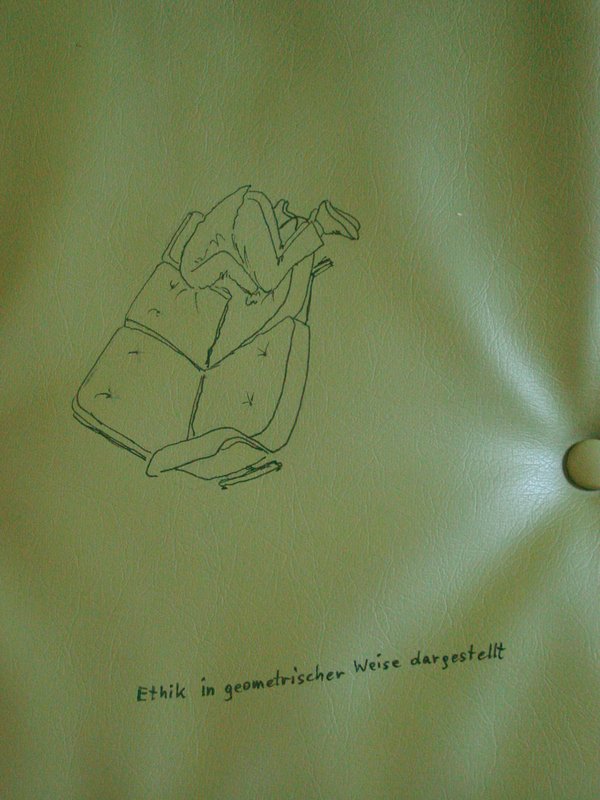

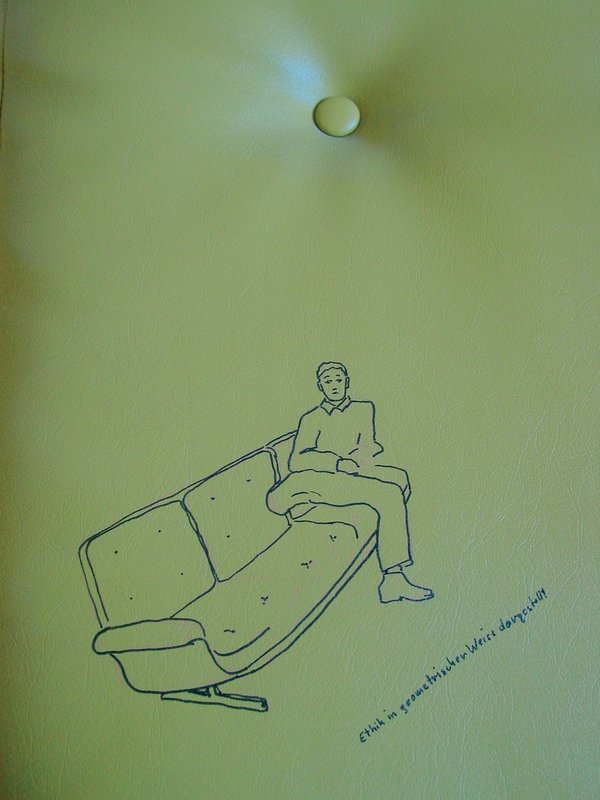

Wurm began his One Minute Sculptures in 1988, and has since been continuously contributing to the encyclopaedic series in myriad locations around the world. As well as photographs, the series comprises video and performance works. The individual photographs feature images of people – anonymous participants, performers, curators, artists and even the artist himself – engaging in unconventional and sometimes physically challenging interactions with everyday objects such as clothing, buckets, balls, doorframes, bicycles and perishable goods. The resulting compositions feature unusual contortions – held for a minute – and illogical still-lives that are both humorous and provocative.

While the photograph is the enduring record of each composition, the work comprises the entirety of the performative process, which begins with Wurm delivering instructions, both written and pictorial, to the subject of the ‘sculpture’. The participant subsequently enacts the determined formation or action and maintains it for a period of sixty seconds, during which time the pose is photographed. In a complex work that explores interaction, activation and the temporal, Wurm employs the photographic medium as a means of cataloguing his ephemeral studies.

Sit Straight, Hold Your Breath and Think About Spinoza, 1999

Ethic Demonstrated in Geometric Order (Spinoza) , 2003

Organisation of Love, 2007